Meditation’s Impact on Cognitive Reserve

Researching Cognitive Reserve yields a few different definitions depending on the source.

From Yaakov Stern, PhD, whose papers on cognitive reserve have been referenced over 2000 times each:

The concept of reserve has been put forward to account for individual differences in susceptibility to age-related brain changes and pathologic changes.

From the Handbook of Neurology, 2015:

Cognitive Reserve refers to how flexibly and efficiently the individual makes use of available brain resources.

From the folks at Harvard Health:

You can think of cognitive reserve as your brain’s ability to improvise and find alternate ways of getting a job done. Just like a powerful car that enables you to engage another gear and suddenly accelerate to avoid an obstacle, your brain can change the way it operates and thus make added resources available to cope with challenges.

And finally, from the fam at Wikipedia:

The mind’s resistance to the damage of the brain.

Taking all of these definitions in, it appears cognitive reserve serves as an indicator of resiliency. The higher the reserves, the greater the brain’s adaptability, the greater the probability of recovery after an adverse event such as injury.

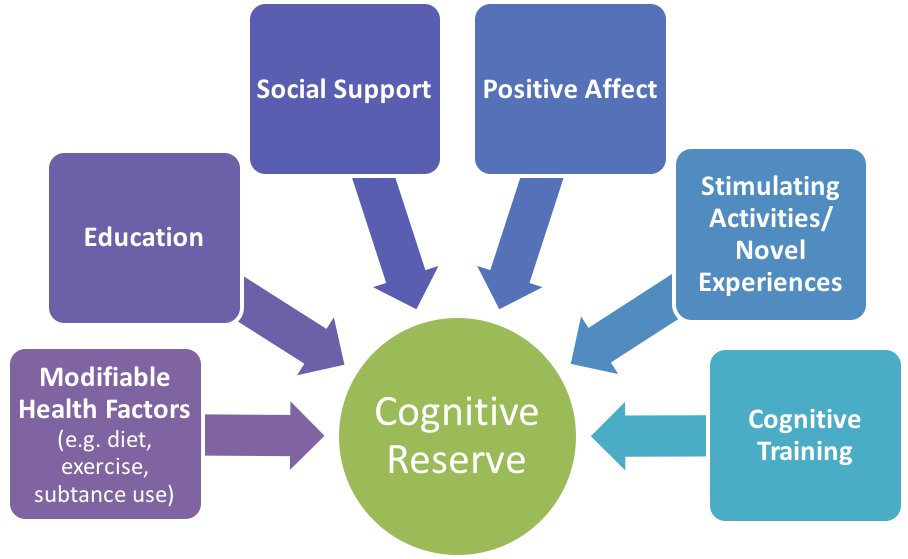

So how do we boost our cognitive reserve? Harvard Health recommends “a lifetime of education and curiosity to help your brain better cope with any failures or declines it faces.”

If this were a newsletter on the benefits of education, we could all simply close our laptops and go to sleep. But, alas, we’re talking about training the mind to become aware of itself, while watching and wondering at the outcomes of such training.

So in the spirit of curiosity I sought to understand the current research landscape linking cognitive reserve and meditation. Here’s what I found.

In one paper, researchers sought to examine the role of mindfulness meditation in building cognitive reserve. To start, let’s define what they mean by mindfulness meditation:

a mental state characterized by “paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (Kabat-Zinn, 2003).

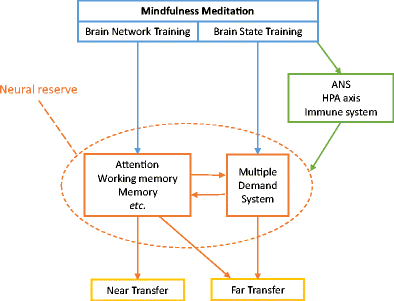

They also emphasized the importance of seeing mindfulness meditation as two types of brain training:

Brain Network Training: improves cognitive abilities by repeatedly engaging the brain networks that are involved in specific cognitive functions.

Brain State Training: involves more general brain states and activates large-scale brain networks that underpin a whole range of cognitive and emotional processes.

Cognition and the prevention of it decline is influenced by a range of non-biological factors, such as level of education, occupational complexity, and leisure activities, to name a few. The cognitive reserve hypothesis aims to explain why a considerable number of older people demonstrate better cognitive performance than their brain pathology predicts. The hypothesis explains that cognitive functions are preserved through 2 different processes:

Neural reserve: the process of sustaining cognitive performance due to higher brain network efficiency, capacity, or flexibility

Neural compensation: the process of recruiting alternative brain networks and structures that are not normally engaged in a certain function.

Example: older adults who recruit bilateral (rather than unilateral) prefrontal areas perform better in cognitive tasks than older adults who do not recruit additional brain regions.

They found that mindfulness meditation may enhance cognitive reserve, potentially even in older individuals suffering from mild cognitive impairment (Larouche et al. 2015; Wells et al. 2013).

In conclusion, brain network training through mindfulness meditation may activate the brain areas involved in attention (Malinowski 2013), working memory (Mrazek et al. 2013) and other specific cognitive processes, thus directly enhancing neural reserve.

While network training enhances specific cognitive functions involved in mindfulness meditation, state training “enhances the large-scale multiple demand system and exerts indirect influence by improving the response functions of autonomic nervous system and immune system.” These improvements in turn have a positive influence on brain structure, such as the hippocampus. Therefore the researchers hypothesized that network training and state training will contribute to neural reserve via direct and indirect routes, respectively.